Inactive and abandoned oil and gas wells in Canada are a much bigger climate problem than previously thought, emitting almost seven times more methane than the official estimates, according to a new study from researchers at McGill University.

The potent greenhouse gas is responsible for a third of all global warming and traps 80 times more heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. But Canada’s efforts to curb methane emissions have focused on active oil and gas sites, rather than those that stopped operating decades ago.

The McGill study says methane emissions from these wells is about 230 kilotonnes yearly, as opposed to the government’s current estimate of 34 kilotonnes.

“Bringing attention to this topic — hopefully that will lead to more emissions reductions, and more development of smart mitigation strategies,” said Mary Kang, associate professor of civil engineering at McGill University, who led the research.

There are about 470,000 non-producing wells across Canada, most in oil-rich Alberta but also in B.C., Alberta and Ontario. Regulators use varying terminology for these wells, like “inactive” or “abandoned,” but they’re generally wells that have ceased production and may require work to plug them and restore the area.

About 68 per cent have been plugged in some way by their owners, while the rest are either unplugged or their status is unknown. The study estimated that about 50,000 wells in Canada are undocumented, most in Ontario.

A new McGill University study suggests that methane leaking from Canada’s abandoned oil and gas wells is almost seven times higher than previously thought, and residents living near them are calling on the government to take urgent action.

The McGill researchers also found that a relatively small proportion of high-emitting wells were responsible for a large portion of the leaks. They suggest targeting those wells, along with repurposing wells for other uses, like producing geothermal energy, which would encourage monitoring them long-term and preventing methane leaks that pop up.

“For example, one well can emit as much as 100 wells combined,” said Jade Boutot, a PhD student in civil engineering who was a co-author on the study.

“When we look at the characteristics of the wells, for example, their location or whether they’re plugged or unplugged, we can identify the wells that are at a higher risk of emitting methane. And then we can prioritize them for remediation.”

Environment and Climate Change Canada says it is reviewing the research and may include it while reviewing how it estimates methane emissions. The estimates are included in the government’s annual greenhouse gas emissions report, which comes out around May.

Living close to the problem

Southwestern Ontario feels a long way from the centre of the oil industry in Western Canada, but it has a long history in oil and gas production. The first commercial oil well in North America started operating in 1858 in Oil Springs, Ont. The industry has left over 23,000 known legacy wells scattered throughout the region.

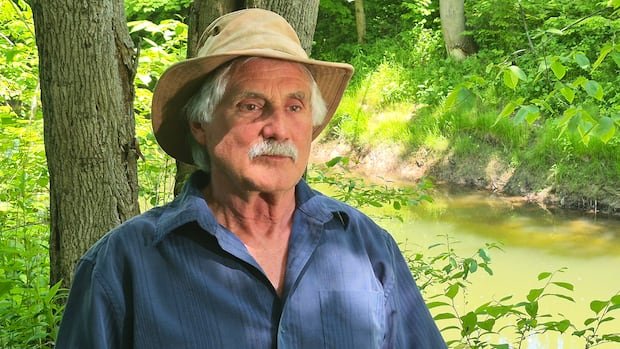

“A lot of the people that were exploiting those wells were actually small landowners and they drilled thousands and thousands of wells that were never recorded,” said Stewart Hamilton, a geochemist and hydrogeologist who works for Montrose Environmental Group, a firm that works on well remediations.

He says he was not surprised at the McGill researchers’ findings, given what he has seen with abandoned wells in Ontario that are leaking into groundwater and the surrounding environment, and causing headaches for local residents.

One such problematic well is in Norfolk County, Ont., about 15 kilometres from the shores of Lake Erie.

“Some days I can’t even go outside without getting burning eyes and a sore throat,” said Paul Jongerden, whose property is along a creek that the well leaks into.

The problem for local residents is hydrogen sulfide, a foul-smelling gas that is ruining their quality of life and causing headaches and other health issues. The well is also leaking methane.

The county has over 2,600 abandoned gas wells, according to recent reports, notes Brian Craig, who also lives near the leaking well.

“This is a very serious issue,” he said. “Many of them have been plugged, but there are many that are still leaking.

“And if you add up all the methane that’s emanating from these gas wells, it is having a serious impact on climate change.”

Fixing leaking wells usually falls to landowners, who complain this puts a huge burden on them, especially when they may not even know how many legacy wells are on their land. This particular well is on land owned by the county, and the local government has been trying to remediate it with help from the province.

“These wells, particularly the wells that have got some underground pressure, they don’t respect municipal boundaries and they don’t respect boundaries in regards to private property and public property,” said Al Meneses, chief administrative officer of Norfolk County.

“What we do is try to get the province to understand that this is a regionwide problem and requires a regionwide solution.”

Ontario’s Abandoned Works Program provides funding to landowners who need to plug wells, and in 2023, the province kicked in $23.6 million to develop a provincewide strategy for dealing with old wells. It included direct funding for counties including Norfolk and a doubling of the Abandoned Works Program’s budget to $6 million annually.

Other provinces have similar programs. Alberta’s Orphan Well Association helps clean up wells whose operators have gone out of business. It raises money through a levy on the oil and gas industry, although critics have warned the levy is not enough to support the work.

In 2020, the federal government announced $1.7 billion to help clean up abandoned wells in B.C., Alberta and Saskatchewan.

“I’m glad that finally, I think this is being taken seriously,” Stewart said.

“It’ll take a long time. But it’s not outside our technical capabilities. We can do it.”

Kang has been researching non-producing wells for over a decade. A landmark study she did in 2014 on non-producing wells in Pennsylvania led the U.S. and Canada to start reporting methane emissions from their non-producing wells in their official yearly estimates.

With the new measurements, Kang says she has a much more representative sample of Canada’s non-producing wells that should improve official estimates.